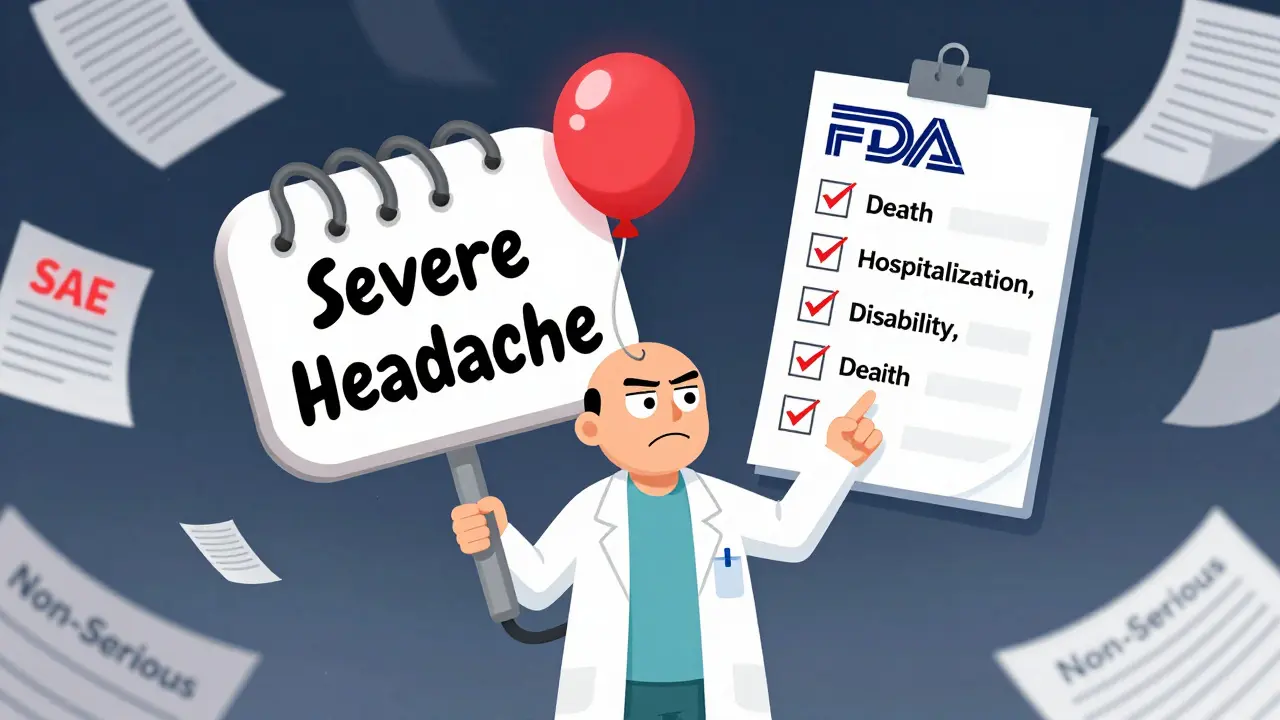

When you're running a clinical trial, every patient reaction matters-but not every reaction needs to be reported the same way. The difference between a serious adverse event and a non-serious one isn't about how bad the symptom feels. It's about what it does to the patient’s life. Confusing severity with seriousness is one of the most common-and costly-mistakes in clinical research.

What Makes an Adverse Event "Serious"?

An adverse event (AE) is any unwanted medical occurrence during a clinical trial, whether or not it’s linked to the drug or device being tested. But only some of these are serious. The FDA and ICH E2A guidelines define a serious adverse event (SAE) by outcome, not intensity. If an event causes any of these six outcomes, it’s serious:

- Death

- Life-threatening condition

- Requires hospitalization or extends an existing hospital stay

- Results in permanent disability or significant incapacity

- Causes a congenital anomaly or birth defect

- Requires medical intervention to prevent permanent harm

Notice what’s missing? "Severe pain" or "intense nausea" doesn’t count. A patient might have a 10/10 headache (severe), but if it goes away with ibuprofen and doesn’t hospitalize them? That’s non-serious. On the flip side, a mild rash that leads to anaphylaxis and ICU admission? That’s serious.

The NIH’s 2018 guidelines make this crystal clear: seriousness is about outcome. Severity is about how much discomfort the patient feels. Mixing them up leads to paperwork overload-and worse, it hides real dangers.

When Do You Have to Report?

Timing is everything. If it’s a serious adverse event, you don’t wait. Investigators must report SAEs to the trial sponsor within 24 hours of learning about them-no exceptions. This applies even if the event seems unrelated to the study drug. The rule isn’t about blame; it’s about speed. Regulatory agencies need to spot patterns fast.

For non-serious events, reporting follows the protocol’s schedule. That could mean monthly summaries, quarterly reports, or even just logging them in the Case Report Form (CRF) without a formal alert. The Data and Safety Monitoring Plan (DSMP) dictates this. If your protocol says to report all grade 2 events monthly, then that’s what you do. But if it’s not serious, it doesn’t trigger an emergency call.

Reporting to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) has its own timeline. SAEs go to the IRB within 7 days. Non-serious events? Often not at all-unless the protocol says otherwise. Many IRBs only review non-serious AEs during routine continuing reviews, saving time and focus for what truly matters.

Why So Much Confusion?

Here’s the hard truth: 37% of SAE reports submitted to IRBs in 2019 were later found to be non-serious. That’s nearly four in ten reports that wasted time, money, and attention. At the University of California, San Francisco, over 40% of AE reports in 2022 needed clarification because someone got the seriousness wrong. In oncology trials-where patients are already frail-the confusion spikes to nearly 80%.

Why? Because "severe" sounds like "serious." A patient with severe depression might be described as "having a serious episode." But unless that depression led to a suicide attempt, hospitalization, or inability to function for weeks? It’s not a reportable SAE. Yet, many coordinators report it anyway-out of caution, or because they’re not trained.

Reddit threads from clinical research coordinators are full of stories: "My PI said anxiety is serious if the patient cries every day." No. Unless it led to self-harm or hospitalization, it’s not. "My patient got a fever of 103°F-should I report?" Only if it caused sepsis, organ failure, or hospitalization. Otherwise, it’s just a fever.

And it’s not just individuals. A 2022 survey of 347 research sites found that 63% had inconsistent seriousness decisions across different studies at the same institution. That’s a systemic problem.

How to Get It Right Every Time

There’s a simple tool: the four-question decision tree from the NIH:

- Did the event cause death?

- Was it life-threatening?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability or significant incapacity?

If the answer to any of these is yes-it’s serious. Report it immediately. If not? Log it as non-serious and follow your protocol’s routine reporting schedule.

Use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) to grade severity (mild, moderate, severe), but keep that separate from your seriousness determination. Most sponsors now use both systems side by side. The FDA’s MedWatch Form 3500A includes checkboxes for each seriousness criterion-use them. They’re there to stop guesswork.

Training is non-negotiable. ICH E6(R2) requires all study staff to be trained on these definitions before the trial starts. And it’s not a one-time thing. 98.7% of top research institutions require annual refresher training. If your site skips it, you’re not just cutting corners-you’re risking patient safety.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

It’s not just about compliance. It’s about money and efficiency. The global clinical trial safety market hit $3.27 billion in 2022. Over 40% of that was spent on managing adverse event reports. And 62.7% of those costs? Came from processing non-serious events that were wrongly labeled as serious.

Think about it: every time a coordinator reports a mild rash as an SAE, someone has to review it, validate it, maybe even call the sponsor, file paperwork, update databases, and notify the IRB. That’s hours of work. Across a single network like SWOG Cancer Research, incorrect classifications consumed 18.5 full-time hours every week.

The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative has processed over 14 million adverse event reports since 2008. Only 18.3% of them were serious. That means over 11 million reports were noise. And that noise drowns out the real signals.

Dr. Janet Woodcock, Director of the FDA’s drug center, put it bluntly: "The system is overwhelmed by non-serious events reported as serious, diluting attention from truly critical safety signals."

What’s Changing?

Things are getting better-but slowly. The European Union’s Clinical Trials Regulation, fully in force since January 2022, standardized seriousness definitions across all 27 member states. That cut cross-border reporting errors by over a third.

The NIH updated its guidelines in September 2023 to clarify that emergency room visits alone don’t make an event serious-unless they meet one of the six criteria. Before that, 22% of non-serious events were misreported just because someone went to the ER.

AI is stepping in. Automated tools now correctly classify seriousness in 89.7% of cases-better than human reviewers at 76.3%. But they’re not replacing people. They’re helping. The FDA’s 2024 pilot program using natural language processing to auto-triage reports is expected to cut processing time by nearly half.

The future is automated triage, standardized definitions, and better training. But until then, the responsibility falls on you: know the six criteria. Use the four questions. Train your team. Don’t let a mild headache become a crisis report.

What If You’re Not Sure?

When in doubt, report it as serious. Then follow up with the sponsor or safety team to confirm. It’s better to over-report once than miss a life-threatening event. But don’t make this your default. Every unnecessary report adds friction to the system. And when the system is clogged, real dangers get missed.

Keep a quick reference sheet on your desk. Print the six criteria. Put the four-question checklist in your protocol binder. Talk to your safety officer. Ask: "Is this about outcome-or just intensity?"

Because in clinical trials, safety isn’t about how loud the alarm is. It’s about whether the alarm means something.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

No, not by itself. A severe headache (pain level 9/10) is intense, but unless it leads to hospitalization, brain hemorrhage, or permanent neurological damage, it’s not a serious adverse event. It’s a severe non-serious AE. Report it per your protocol’s routine schedule.

Do I report an AE if it’s not related to the study drug?

Yes. Serious adverse events must be reported regardless of whether they’re believed to be related to the investigational product. The rule is based on patient outcome, not causality. Even if you think the event is coincidental, if it meets the six seriousness criteria, report it immediately.

What’s the difference between a Grade 3 and a serious AE?

Grade 3 in CTCAE means severe symptoms requiring medical intervention, but it doesn’t automatically make an event serious. For example, a Grade 3 nausea that responds to antiemetics without hospitalization is still non-serious. Seriousness depends on outcome: death, hospitalization, disability, etc. Always check the six criteria-not just the grade.

Can an event be serious even if it’s mild in intensity?

Yes. A mild rash that triggers a life-threatening allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) is a serious adverse event-even though the rash itself was mild. Similarly, a mild fever that leads to sepsis and ICU admission is serious. Outcome overrides intensity every time.

Do I need to report non-serious AEs to the IRB?

Usually not. Most IRBs only require non-serious adverse events to be reported during routine continuing reviews, unless the protocol specifies otherwise. Always check your study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Plan. Many protocols exclude non-serious AEs from IRB reporting entirely to reduce administrative burden.

What happens if I report a non-serious event as serious?

It wastes time, money, and attention. Every misclassified event triggers a review, documentation, and potential regulatory scrutiny. In 2020, nearly 29% of expedited safety reports across Europe didn’t meet seriousness criteria. That’s a systemic drain. While not usually punished, repeated errors lead to audits, retraining, and delays in trial progress.

Post A Comment