When you hear the word biosimilar, you might think it’s just a cheaper version of a biologic drug - like a generic pill but for injectables. But here’s the thing: biosimilars aren’t generics. They’re not chemically identical. They’re made from living cells, and even tiny differences in how those cells are grown or processed can change how your body reacts to them. That’s where immunogenicity comes in - and why some patients might respond differently to a biosimilar than to the original biologic.

What Exactly Is Immunogenicity?

Immunogenicity is just a fancy way of saying: your immune system might see this drug as a threat. When that happens, your body starts making antibodies against it. These are called anti-drug antibodies, or ADAs. For some drugs, especially biologics like infliximab or adalimumab, this isn’t rare. Studies show up to 70% of patients on certain monoclonal antibodies develop ADAs over time. The problem isn’t just that antibodies are there. It’s what they do. Some ADAs just stick to the drug and tag it for removal - your body clears it faster, so it stops working as well. Others, called neutralizing antibodies, actually block the drug from doing its job. In rare cases, they can trigger serious reactions like anaphylaxis. That’s what happened with cetuximab, where a sugar molecule on the drug caused IgE-mediated allergic shocks in some patients.Why Do Biosimilars Sometimes Trigger Different Reactions?

Biosimilars are designed to be nearly identical to their reference products. But because they’re made in living systems - usually Chinese hamster ovary cells or human cell lines - small changes creep in. These aren’t mistakes. They’re unavoidable side effects of biology. Think of it like baking two loaves of sourdough from the same recipe. Same flour, same yeast, same oven. But one loaf has a slightly thicker crust because the baker opened the door twice. That’s what happens with biosimilars. Minor differences in:- Glycosylation - the sugar chains attached to the protein

- Sialylation - how many sialic acid molecules are present

- Aggregation - clumps of protein that form during storage or handling

- Host cell proteins - leftover bits from the manufacturing cells

It’s Not Just the Drug - It’s You Too

Your body plays a huge role. Two people on the exact same biosimilar might have totally different immune responses - because their immune systems are different.- Genetics: People with the HLA-DRB1*04:01 gene variant are nearly five times more likely to develop ADAs to certain biologics.

- Disease state: Someone with rheumatoid arthritis has 2.3 times higher risk than a healthy person. Their immune system is already revved up.

- Other meds: Taking methotrexate with a TNF inhibitor cuts ADA risk by 65%. It’s like a quieting agent for your immune system.

- Route of delivery: Shots under the skin (subcutaneous) are more likely to trigger ADAs than IV infusions. Why? Because the immune system in your skin is more active than in your bloodstream.

- Dosing schedule: If you get the drug every few weeks instead of continuously, your immune system has time to react between doses.

How Do We Even Measure This?

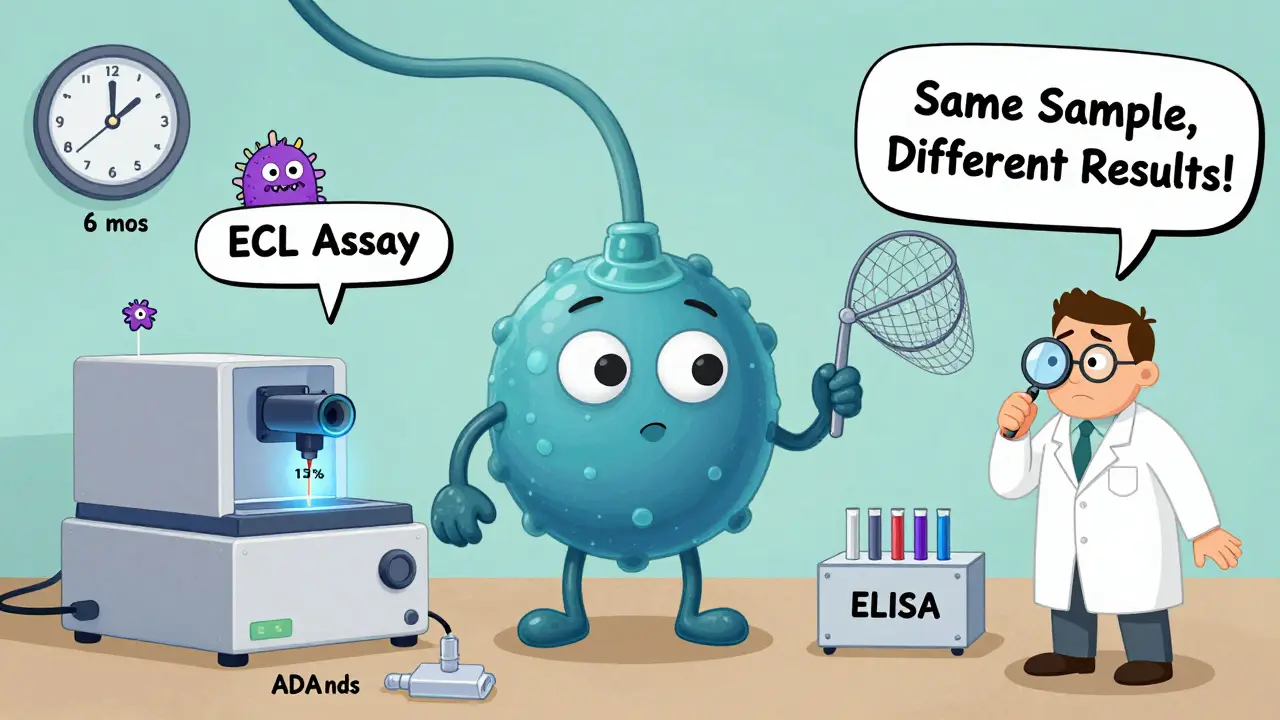

This is where things get messy. Not all tests are created equal. The FDA and EMA require biosimilar manufacturers to test for immunogenicity using a tiered approach: screening, confirmation, then characterization. But here’s the catch - different labs use different tools. One might use electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays, which are super sensitive and can detect ADAs in 13.1% of patients. Another might use ELISA, which misses a lot of those same cases. That’s why comparative studies must use the same method, on the same samples, at the same time. Otherwise, you’re not comparing drugs - you’re comparing lab techniques. Dr. John Faradji from BioAgilytix says it plainly: “The choice of assay directly impacts immunogenicity findings.” And even then, neutralizing antibody tests are tricky. Cell-based assays - which show if the antibody actually blocks the drug’s function - are considered more accurate. But they’re less precise, with variability up to 30%. That’s like flipping a coin three times and getting heads, tails, heads - you can’t be sure what the pattern really is.Real-World Evidence: Do Differences Actually Matter?

Let’s cut through the theory and look at what’s happening in clinics. A 2021 study of 1,247 rheumatoid arthritis patients found no difference in ADA rates between reference infliximab and its biosimilar CT-P13 (12.3% vs. 11.8%). Another big trial, NOR-SWITCH, followed 481 patients switched from originator to biosimilar. The biosimilar group had slightly more ADAs (11.2% vs. 8.5%), but no drop in effectiveness or increase in side effects. Then there’s the 2020 Danish registry data: for adalimumab, the reference product had 18.7% ADA rates, while the biosimilar Amgevita hit 23.4%. Statistically different. But here’s the twist - both groups had the same clinical outcomes. No more flare-ups, no more hospital visits. Patient forums tell a different story. On Reddit’s r/rheumatology, one user reported severe injection site reactions after switching to a biosimilar etanercept - reactions they never had with the original. Another said they switched back and forth between Humira and its biosimilar for three years and noticed zero difference. A 2022 survey of 347 rheumatologists showed 68% think immunogenicity fears are overblown. But 22% say they’ve seen real, clinically meaningful differences in practice. So it’s not black and white.

The Regulatory Gap

Regulators require biosimilars to prove “no clinically meaningful differences” from the reference product. But what does that mean? If a biosimilar has 5% higher ADA rates but the same clinical effect - is that meaningful? The FDA says yes - if the difference could lead to loss of efficacy or safety risks. The EMA says the same. But the real problem? Many biosimilars are approved based on data from healthy volunteers or short-term trials. That’s not enough. Biologics are often used for years. Immune tolerance builds slowly. You might not see ADAs until after six months. And here’s another blind spot: formulation. The biosimilar version of rituximab (Rixathon) uses polysorbate 80 as a stabilizer. The original (Rituxan) uses polysorbate 20. These are similar but not identical. One might cause more protein aggregation. That’s enough to change immunogenicity - even if the protein itself is identical.What’s Next?

The future is in precision. We’re moving beyond just checking if two proteins look alike. Now scientists are using:- Glycomics - mapping every sugar on the protein

- Proteomics - identifying every variant form of the protein

- Immunomics - testing how patient immune cells react to each version

Bottom Line

Biosimilars are safe. They work. For most people, switching to one makes no difference at all. But immunogenicity isn’t a myth. It’s a real, measurable, sometimes unpredictable risk. And it’s not just about the drug - it’s about the patient, the manufacturing process, the delivery method, and how we test for it. The key takeaway? Don’t assume biosimilars are interchangeable in every way. Track your response. If you switch and start having new side effects - especially injection site reactions, fatigue, or reduced effectiveness - talk to your doctor. It might not be your disease flaring. It might be your immune system reacting to a new version of the drug. The goal isn’t to scare people away from biosimilars. It’s to make sure we treat them like the complex biological products they are - not just cheaper copies.Are biosimilars the same as generics?

No. Generics are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts - they’re exact copies made from synthetic chemicals. Biosimilars are made from living cells, so they’re highly similar but not identical. Even tiny differences in structure - like sugar attachments or protein folding - can affect how your immune system responds.

Can a biosimilar cause more side effects than the original biologic?

It’s possible, but rare. Most studies show no major difference in safety. However, some patients develop more anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) with biosimilars, which can lead to injection site reactions, reduced drug effectiveness, or - in very rare cases - allergic reactions. These aren’t common, but they’re real enough that doctors monitor for them.

Why do some patients react differently to biosimilars than others?

Your immune system is unique. Factors like genetics, existing diseases (like rheumatoid arthritis), other medications (like methotrexate), and even how often you get the shot can all influence whether your body reacts. Two people on the same biosimilar might have totally different outcomes - not because the drug is different, but because their bodies are.

Do all biosimilars have the same risk of immunogenicity?

No. Different biosimilars have different manufacturing processes. Some use different cell lines, stabilizers, or purification methods. Even small changes - like switching from polysorbate 20 to polysorbate 80 - can affect protein stability and increase aggregation, which raises immunogenicity risk. Each biosimilar must be evaluated on its own.

How do doctors test for immunogenicity?

They use blood tests to detect anti-drug antibodies (ADAs). The most common method is a screening test, followed by a confirmatory test to rule out false positives. For neutralizing antibodies, doctors may use cell-based assays that show whether the antibodies actually block the drug’s function. But testing isn’t routine - it’s usually done in research settings or if a patient suddenly stops responding.

Should I avoid biosimilars because of immunogenicity risks?

For most people, no. Biosimilars are rigorously tested and have been used safely for over 15 years. The benefits - lower cost and increased access - far outweigh the risks for the vast majority of patients. But if you’ve had a bad reaction to a biologic before, or if you notice new symptoms after switching, talk to your doctor. Don’t assume all versions are the same.