When a pharmacist pulls a prescription off the system, they’re not just filling a bottle-they’re making a decision that affects safety, cost, and trust. The difference between a brand-name drug and its generic version isn’t just in the label. It’s in how the pharmacy system identifies it, what alerts it triggers, and whether the patient even knows what they’re getting. Getting this right isn’t optional. It’s foundational.

Why Generic vs Brand Identification Matters

Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. That’s not because they’re cheaper by accident-it’s because they’re proven to work the same way. The FDA requires generics to match brand-name drugs in active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and how the body absorbs them. But here’s the catch: not all systems treat them the same.

Imagine a patient on warfarin. Even a tiny variation in blood levels can lead to a stroke or dangerous bleeding. If the pharmacy system doesn’t flag that this is a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug, it might automatically swap the brand for a generic without warning. That’s not just a mistake-it’s a risk. Systems that ignore therapeutic equivalence codes or fail to distinguish between authorized generics and branded generics put patients in danger.

The real problem isn’t the drugs. It’s the data. Pharmacy systems rely on the National Drug Code (NDC), the FDA’s Orange Book, and Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) codes to tell them what’s what. If those systems aren’t updated, misconfigured, or poorly trained, the wrong drug gets dispensed-even if it’s technically "equivalent."

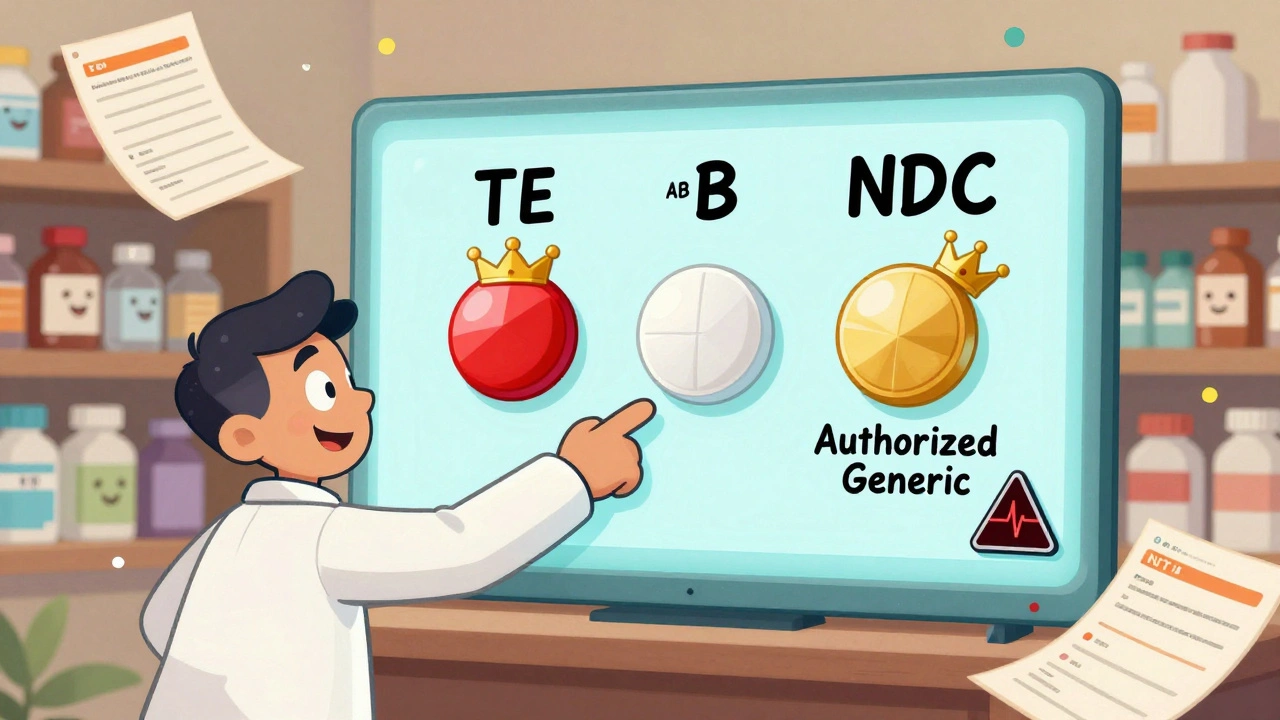

The Anatomy of Drug Identification: NDC, TE Codes, and the Orange Book

Every drug in the U.S. has a unique 10- or 11-digit NDC. It looks like this: 00026-1234-56. The first part is the labeler (manufacturer), the second is the product (strength and form), and the third is the package size. But here’s what most people don’t realize: a brand-name drug and its generic version have different NDCs. That’s not an error-it’s by design.

The FDA’s Orange Book is the gold standard for therapeutic equivalence. It assigns each drug a TE code. If it starts with an "A," like AB or AO, it’s considered interchangeable with the brand. If it’s "B," it’s not. Systems that ignore TE codes are flying blind. For example, levothyroxine has over 40 different generic versions. Some are AB-rated. Others aren’t. A system that treats them all the same is setting up a patient for thyroid instability.

Then there’s the mess of authorized generics. These are the exact same pills as the brand, just sold under a generic label. They’re made by the same company, same factory, same batch. But pharmacy systems often can’t tell them apart from other generics because they use the same NDC format. That’s why some pharmacists see 17 different versions of lisinopril-and have no idea which one is the authorized generic. The only way to know is to cross-check the FDA’s NDA number. If it matches the brand’s, it’s an authorized generic.

Branded Generics: The Hidden Trap

Not all generics look like generics. Some, like Errin, Jolivette, and Sprintec, have catchy names. They’re not brand-name drugs. They’re generics that went through the ANDA process but were given a branded name for marketing. They’re chemically identical to other generics. But if your system shows "Sprintec" as the default, and the prescriber wrote "birth control pill," the pharmacist might assume it’s the brand. It’s not. It’s a generic. And if the patient’s insurance only covers the true generic, they’ll be charged more-or worse, denied.

This confusion is especially common with oral contraceptives, antidepressants, and blood pressure meds. A 2022 survey found 78% of pharmacists reported difficulty distinguishing branded generics from true brands. The fix? Systems need to show the chemical name alongside the brand name. If the system says "Sprintec (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol)," the pharmacist knows instantly: this is a generic, even if it looks like a brand.

How Systems Should Be Configured: The 3-Tier Best Practice

High-performing pharmacy systems don’t just display drugs-they guide decisions. The best ones follow a three-step protocol:

- Default to generic names in all order entry and dispensing screens. Over 90% of EHR systems now do this. It reduces errors and encourages cost savings.

- Enforce TE code checks before substitution. If a drug is NTI (like warfarin, phenytoin, or levothyroxine), the system should block automatic substitution unless overridden by a prescriber with a clear reason.

- Flag authorized and branded generics with visual indicators. A small icon, color code, or text note like "Authorized Generic - Same as Brand" makes all the difference.

Systems like Epic, Cerner, and Rx30 can do this. But they need setup. A single pharmacy workstation can take 15-20 hours to configure correctly. That’s not a cost-it’s an investment in safety. Kaiser Permanente, for example, achieved a 92.7% generic dispensing rate in 2022 by setting generics as default and adding patient education pop-ups at the counter. Their brand continuation requests dropped by 37%.

Where Systems Fail: NTI Drugs, Excipients, and Communication Gaps

Even the best systems have blind spots. The FDA doesn’t require generic manufacturers to match inactive ingredients (excipients) like fillers or dyes. That’s fine for most people. But for someone with a rare allergy or severe Crohn’s disease, a different dye can cause a reaction. A 2019 study found 0.8% of patients switching from brand to generic antiepileptic drugs reported new side effects-likely due to excipients. Pharmacy systems don’t track this. They should.

Then there’s communication. A 2020 U.S. Pharmacist report found 68% of patients didn’t know generics had the same active ingredients. If a patient gets a different-looking pill and no one explains why, they might stop taking it. Or worse, they might think it’s fake. The fix? Simple visual aids at the counter. A card that says: "This is a generic version of [Brand Name]. Same medicine. Lower cost. Same results." That’s not extra work-it’s essential.

And don’t forget state laws. California requires pharmacists to document why they didn’t substitute a generic. Texas lets them substitute without asking. A system that doesn’t adjust for state rules will generate compliance errors. That’s why systems need location-based rules built into their logic.

What’s Next: AI, Real-Time Updates, and the Future of Identification

The FDA’s 2023 Orange Book modernization is a game-changer. For the first time, it’s being released as a machine-readable API with real-time updates. That means pharmacy systems can now get new generic approvals within hours-not weeks. No more waiting for manual database updates.

AI is stepping in, too. A 2023 study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association showed AI models could predict therapeutic equivalence issues with 87.3% accuracy by analyzing prescription patterns. If a patient switches from one generic to another and their INR spikes, the system can flag it-not as a random event, but as a potential bioequivalence problem.

Future systems will tie into pharmacogenomics. If a patient has a genetic variant that affects how they metabolize levothyroxine, the system could suggest sticking with a specific brand-even if a generic is cheaper. That’s not science fiction. The FDA’s Precision Medicine Initiative is already exploring it.

What Pharmacists and Pharmacies Can Do Today

You don’t need a $500,000 system to get this right. Start here:

- Verify your system pulls data from the FDA Orange Book and DailyMed-monthly updates aren’t enough. Set alerts for weekly changes.

- Train every technician and pharmacist on TE codes. Don’t assume they know what "AB" means. Show them examples.

- Create a cheat sheet: "If it’s NTI, pause. If it’s authorized generic, note it. If it’s branded generic, clarify the chemical name."

- Put patient education materials at the pickup counter. One card. One sentence. One image.

- Push back on vendors who don’t support real-time API updates. If your system can’t get new generics within 48 hours, it’s outdated.

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system billions every year. But savings mean nothing if patients don’t trust them-or if they get hurt because the system got confused. The tools are here. The data is available. The only thing missing is consistent implementation.

Are generic drugs really the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes, when approved by the FDA. Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also be bioequivalent-meaning they work the same way in the body. The FDA requires generics to meet the same quality and safety standards as brands. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, packaging, and price.

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

An authorized generic is made by the same company that makes the brand-name drug, often in the same factory, using the same ingredients and process. It’s sold under a generic label at a lower price. A regular generic is made by a different company that’s proven bioequivalence through the ANDA process. Authorized generics are identical to the brand; regular generics are therapeutically equivalent but may differ in inactive ingredients.

Why do some pharmacy systems still show brand names as defaults?

Some systems default to brand names because of legacy settings, vendor defaults, or prescriber preferences. But this increases costs and confusion. Best practice is to default to generic names unless there’s a clinical reason not to. Systems that do this see higher generic utilization, fewer errors, and better patient outcomes.

Can I substitute any generic for a brand-name drug?

Not always. For narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and phenytoin, even small differences can be dangerous. Most states allow substitution only if the generic is rated "AB" by the FDA. Even then, many systems require a prescriber override. Never assume substitution is automatic-check the TE code.

How do I know if a generic is really equivalent?

Look up the drug in the FDA’s Orange Book using its NDC or active ingredient. If it has an "AB" therapeutic equivalence code, it’s rated interchangeable. You can also check if it’s an authorized generic by comparing the NDA number to the brand’s. If they match, it’s the exact same product.

What should I do if a patient reports side effects after switching to a generic?

Don’t dismiss it. While most side effects aren’t due to bioequivalence, they can be caused by inactive ingredients, packaging changes, or psychological factors. Document the reaction, check the excipients, and consider switching back or to a different generic. Some patients need to stay on a specific brand or authorized generic. Patient reports are valuable data-use them to improve your system.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Brand-It’s About Accuracy

The goal isn’t to push generics over brands. The goal is to make sure the right drug gets to the right patient, at the right price, with the right information. Whether it’s a brand, an authorized generic, or a branded generic-the system should know. The pharmacist should know. And the patient should know. That’s what best practice looks like.

Post A Comment