Most people think they know how much they sleep. But if you’ve ever woken up feeling exhausted despite spending eight hours in bed, you’re not alone. The truth is, sleep efficiency-the percentage of time in bed actually spent asleep-is often wildly different from what we guess. That’s where actigraphy and modern wearables come in. They don’t just count hours; they track patterns, expose hidden wakefulness, and reveal whether your sleep is truly restorative.

What Actigraphy Really Measures

Actigraphy isn’t magic. It’s motion. A tiny accelerometer in a wristband, ring, or watch records every shift, twitch, and roll you make during the night. Then, software turns that movement into a guess: asleep or awake. It’s not measuring brainwaves like a sleep lab. It’s watching your body. And that’s exactly why it works for home use.Unlike polysomnography (PSG), which requires a hospital visit and only captures one or two nights, actigraphy can go for weeks. You wear it while you cook, commute, and binge-watch shows. That’s the big win: real life, not a lab. It catches patterns you’d never notice-like sleeping later on weekends, or waking up at 3 a.m. every Tuesday. It’s especially useful for people who think they’re not sleeping at all, but are actually resting quietly. That’s called paradoxical insomnia, and actigraphy can prove it’s not in your head-it’s in your perception.

How Modern Devices Work

Today’s wearables use tri-axial accelerometers, meaning they track movement in all three directions: up-down, side-to-side, and front-back. Some, like the GENEActiv, sample at 100Hz-100 times per second. That’s more than enough to catch even the tiniest shifts. But raw motion isn’t enough. Algorithms turn that data into sleep estimates. They look for long stretches of stillness (likely sleep) and bursts of movement (likely wakefulness).But here’s the catch: if you lie perfectly still while awake, the device thinks you’re asleep. That’s the biggest flaw. Studies show actigraphy can misidentify wake time as sleep 20% to 70% of the time, depending on the person and the device. That’s why newer models are adding more sensors. The Oura Ring, for example, also tracks your skin temperature and heart rate variability. Garmin’s latest algorithm includes heart rate data to better spot when you’re awake but motionless. These upgrades help, but they’re still estimates.

Medical vs. Consumer Devices

Not all wearables are created equal. There’s a big gap between what doctors use and what you buy online.Clinical-grade devices like the Philips Actiwatch Spectrum Plus cost between $1,200 and $1,800. They’re FDA-cleared, designed for sleep specialists, and come with software that lets clinicians analyze data in detail. They’re used to confirm circadian rhythm disorders, track treatment progress for insomnia, or monitor shift workers.

Consumer devices-Fitbit, Oura, Apple Watch, Garmin-are cheaper. The Fitbit Charge 5 runs $99. The Oura Ring Gen 3 is $299. They use similar motion-sensing tech, but their algorithms are optimized for mass appeal, not medical accuracy. They’ll tell you you slept 7 hours and 12 minutes. They’ll even break it into “light,” “deep,” and “REM” sleep. But here’s the thing: Stanford researchers found these stage estimates are often off by 30 minutes or more compared to lab PSG.

So if you’re trying to diagnose sleep apnea or narcolepsy, wearables won’t cut it. But if you want to see whether your bedtime routine is actually helping, or if your jet lag is lasting longer than it should? They’re powerful tools.

What Metrics Actually Matter

Don’t get distracted by fancy sleep stages. Focus on three numbers:- Total Sleep Time: How many hours you actually slept, not how long you lay in bed.

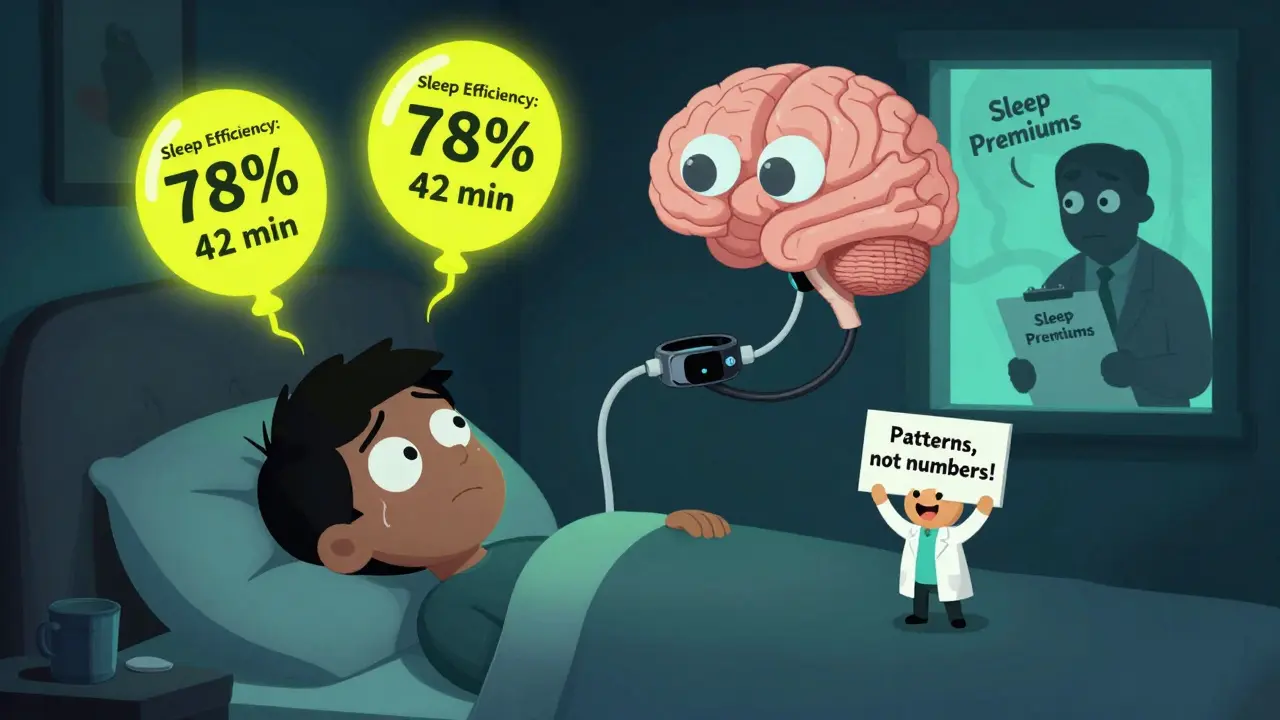

- Sleep Efficiency: (Total Sleep Time ÷ Time in Bed) × 100. Anything below 85% for more than a week is a red flag.

- Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO): How many minutes you spent awake after falling asleep. More than 30 minutes consistently? Your sleep is fragmented.

These numbers don’t lie. If your sleep efficiency drops below 80% for three nights in a row, something’s off. Maybe it’s caffeine after 2 p.m. Maybe it’s stress. Maybe you’re sleeping in a room that’s too warm. Wearables won’t fix it-but they’ll show you when to look closer.

How to Use Them Right

Wearing the device isn’t enough. Here’s how to get real value:- Wear it on your non-dominant wrist. Studies show misplacement cuts accuracy by up to 22%.

- Wear it for at least 7 days. One night doesn’t tell you anything. You need a baseline.

- Don’t remove it for more than 2 hours a day. That’s the threshold where data becomes unreliable.

- Log your habits: when you drank coffee, if you exercised, if you were stressed. Correlation is key.

- Ignore single-night spikes. Sleep varies naturally. A 30- to 45-minute difference from night to night is normal.

Most people think the app is the answer. But the real insight comes from looking at trends over weeks. If your sleep efficiency improves after switching off your phone at 10 p.m., that’s your win-not the number on your dashboard.

What the Experts Say

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine says actigraphy has “moderate evidence” for tracking insomnia in adults-but “low evidence” for diagnosing specific disorders. That means: don’t self-diagnose sleep apnea from your Fitbit. Don’t skip a doctor’s visit because your ring says you slept well.Dr. Cathy Goldstein from the University of Michigan puts it plainly: “Actigraphy provides valuable real-world data but should complement rather than replace clinical evaluation.”

And Dr. Mathias Basner at the University of Pennsylvania warns that consumer devices often overpromise. “Marketing claims create false confidence,” he says. “People think they’re getting medical-grade data, but they’re not.”

But here’s what most experts agree on: if you’re trying to change your sleep habits, wearables help. A 2023 Consumer Reports survey found 78% of users felt more motivated to improve sleep after using trackers for a month. That’s huge. Behavior change starts with awareness.

Privacy and Pitfalls

There’s another side. Your sleep data is deeply personal. And most apps don’t protect it well. Security researcher Alex Birsan found that many consumer sleep apps send raw actigraphy data without end-to-end encryption. That means your sleep patterns could be sold, leaked, or even used by insurers down the line.Senator Tammy Duckworth raised this in a 2024 Senate hearing. Insurance companies might one day ask for your sleep data to set premiums. Employers might use it to judge “wellness.” You’re not just tracking sleep-you’re generating a health profile that could be weaponized.

And then there’s orthosomnia. That’s when tracking sleep makes you anxious. You start obsessing over a 2% drop in sleep efficiency. You lie awake trying to “perform” better. It’s ironic: a tool meant to help sleep ends up stealing it.

What’s Next

The field is moving fast. In 2024, the NIH funded a $2.8 million project at the University of Michigan to build AI that improves wake detection by 27%. Apple is rumored to be launching a “Sleep Study” feature for the Apple Watch that combines actigraphy with audio and temperature sensing. Garmin’s new algorithm already uses heart rate variability to cut false wake detections by 16%.By 2027, experts predict 80% of primary care clinics will use some form of actigraphy in wellness checks. But the goal isn’t to replace doctors-it’s to give them better data. Think of it like a blood pressure cuff for sleep: a snapshot of your body’s rhythm, not a diagnosis.

The future isn’t about perfect numbers. It’s about patterns. If your sleep efficiency drops every time you work late, that’s your clue. If you sleep better on weekends but crash on Monday mornings, that’s your rhythm talking. Wearables don’t fix sleep-they reveal what’s broken. And once you see it, you can finally do something about it.

Post A Comment